Evaluation - Documentation Centre Athens 2007-2009

ANTWERPEN

In the autumn of 1990 Eric Antonis was put in charge of the project that was to make

Antwerp the cultural capital of Europe in 1993.

ANTWERP 93 was to be a European project with a distinct emphasis on (contemporary) art

and it would aim to leave its mark in the longer term.

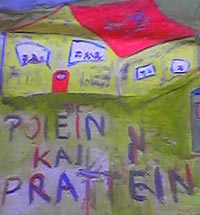

ANTWERP 93’s policy plan made a conscious choice in favour of art: in favour of nuance,

criticism, asking questions, exploring doubts and looking for answers. Furthermore, it

expressly opted to create: to bring new texts, new pieces of music, new works of art, new

theatre productions – and in this way, ANTWERP 93 also showed it was prepared to take

risks.

Eight programmes, each relating to a specific sector, were developed:

Historical Projects, Music, Performing Arts, Discourse and Literature, Architecture and Urban Development, Film, Photography and Media Art, Contemporary Visual Art and Large-Scale Projects.

Two projects by independent organisers, relating to fashion and silver, were brought together

in a ninth Applied Art ‘sector’.

A Distant City: Historical Exhibitions The ANTWERP 93 programme of historical exhibitions served to draw public attention to the contributions Antwerp made to European culture.

Jacob Jordaens (1593-1678) was a large-scale exhibition which brought an overview of the

oeuvre of the Antwerp baroque painter, who is often referred to in the same breath as his

fellow townsmen and contemporaries, Rubens and Van Dyck.

The Rubens Cantoor exhibition showed drawings which his pupil Willem Panneels copied

from Rubens’ own studies. The exhibition, mounted at Rubens’ House, juxtaposed work by

the pupil with originals by Rubens.

The Panoramic dream. Antwerp and the Word Fairs used objects, illustrations and

reconstructions to evoke a picture of the three Antwerp expos, in 1885, 1894 and 1930.

They reflected an aspect of the mentality of the times, mirroring the West’s belief in its

domination and superiority and in eternal progress.

Antwerp, Story of a Metropolis (16th-17thcenturies) told the story of Antwerp’s sudden rise

as a Metropolis around 1500, its relatively short lived hey-day in the 16th century and is

glorious twilight years in the 17th century.

Listening to the city: Music

The ANTWERP 93 programme consisted mainly of ‘serious’ music. On the other hand, other

cultures were included and ANTWERP 93 programmed Moroccan, Jewish, Spanish, Indian

and Indonesian music. The Carrier Pigeons and Coloured Pencils project brought young

people from Antwerp’s Moroccan community into contact with local and Moroccan

teachers.

Most of ANTWERP 93’s more than one hundred concerts were of classical music. Two series

of concerts of early music, the first devoted to the Flemish polyphonists and their

contemporaries, the other to Monteverdi brought internationally celebrated performers to

Antwerp.

The music programme also provided real scope for concerts of contemporary

music with Karel Goeyvaerts’ Aquarius as the finale and the climax.

Twenty composers received commissions from ANTWERP 93, and nineteen of these

compositions were premiered in 1993.

Theatre, Dance, Opera: Performing Arts

The newly-restored Bourla theatre was the venue for seven theatre productions, mostly

creations.

Contemporary dance in Flanders always receives great attention. In association with

deSingel, ANTWERP 93 staged Mozart/Concertarias by Anna Theresa De Keersmaeker to

music by the Orchestre des Champs-Elisées conducted by Philippe Herreweghe.

The Ballett

Frankfurt danced three productions in Antwerp:

Limb’s Theorem and the Loss of Small Detail by Forsythe and

The Sound of One Hand Clapping by Fabre.

Fabre’s production, Daun’altra faccia del tempo was also staged, as was the Slovenian project

Noordung.

The Trisha Brown Company provided a last great moment of dance with two different

programmes including Another Story as in Falling.

Antwerp 93 also organized a festival of contemporary opera. It brought four operas and

Flemings collaborated on each of them. Three of these were creations:

Orfeo (Hus/Lauwers),

Red Rubber (D’haese/Steyermark),

Missa e Combattimento (Monteverdi/Weir).

Silent screams, difficult dreams (Knapik/Fabre) was the fourth opera.

Singling out the Book: Discourse and Literature

ANTWERP 93 chose to create a sharply-defined, international literary project, designed to

enrich the existing one. This project, Discourse and Literature, produced five publications.

The important work 'Occupied City', by the Antwerp poet Paul Van Ostaijen, was at last

translated into French: Ville Occupée and was published in a special edition as a true replica of

the first Dutch-language publication.

Nouvelle Synthèse d’Anvers provided a literary artistic reflection on urbanity and on the

city of Antwerp.

The most important publication was the series of six Cahiers. Each Cahier comprises twelve

texts relating to a specific theme. The Cahiers are a collection of a total of 100 texts, of

which 90 were new and written on request.

Discourse and Literature’s final publication was Het vel van Cambyses (The sheet of

Cambyses), two volumes and an epilogue designed to provide the art critic in Flanders with

an infrastructure by bringing together a choice of good art review texts. One book deals

with visual arts, the other with theatre, dance, opera, film, photography and television.

For a City Culture: Urban Development and Architecture

Open City, ANTWERP 93’s Urban Development and Architecture programme, focussed on

the concepts of ‘city’ and ‘urbanity’. The programme aimed to concentrate the thoughts

of a wide public on the urban phenomenon, to encourage international exchange, to

escape the disciplinary straitjacket of urban planning and architecture and conversely to

work towards achieving a city culture.

In Open City Studio young European researchers from various disciplines spent nine months

working intensively alongside academics, field-workers and critics from home and abroad.

Open seminars examined various aspects of a city culture.

Open City Forum comprised three series of lectures and four colloquia.

The real city of Antwerp served as the starting point and touchstone through the entire

Open City programme. It tried to let people experience the reality and potential of the

problem areas of the city, by means of the photographic exhibition (Sub)urban Landscapes,

a series of peeping boxes, and above all the tremendously successful City Trails (3.121 walks).

In three international colloquia, Open City also drew attention to the problem of intolerance with regard to minorities and immigrant groups.

Film, Photography and Media Art

ANTWERP 93 presented several photographic exhibitions. In A City in Photographs, five

celebrated European photographers recorded their impressions of Antwerp.

The newly-restored Cathedral provided the setting for the unusual Camera Gothica exhibition whose 19th-century photographs took ecclesiastical Gothic architecture as their

subject.

In terms of media art, ANTWERP 93 presented nine creations (films or installations), all

except one realised by Flemish artists.

The Retrospective of Belgian Video Installations exhibition showed how Belgian artists

have played a leading role in the field of media art in recent decades.

On a triptych: Contemporary Visual Art

The New Sculptures project set out to give a new impetus to the collection at Middelheim

Open-air Sculpture Museum. The existing collection was reorganised and ten sculptures by

contemporary European artists were purchased with a view to extending the collection.

The Sublime Void brought an exhibition of work by artists who make the past live again by

means of atmosphere, title or form.

The exhibition On taking a normal situation ...compared and examined the validity of

various exhibition models and placed the emphasis on the relationship between the work

of art and the cultural and spatial environment in which it originated or in which it is

shown. Eighteen, mainly young, artists were commissioned to show new work.

A Dream for a City: ANTWERP 93’s Large-Scale Projects

The large-scale events during the summer were chosen as a means of communication, as

the creation of an unusual and inviting framework in which a large public would come face

to face with an interesting artistic interpretation.

In the five different locations, the large-scale events would enter into a committed relationship with their surroundings. Special attention was paid here to Antwerp’s multicultural aspect.

Sanfte Struckturen brought together local residents and international volunteers, under the

leadership of Marcel Kalberer, with a view to building a village made of branches.

The horses opera Zingaro combines dance theatre, dressage, circus and ethnic music to

form an attractive concept.

Le Cargo, a cargo ship with a narrow little Nantes street reconstructed down in its hold,

moored at the old port area of Antwerp. The setting provided the decor for some eighty

concerts of traditional European music in the space of four weeks.

Les Embouteillages was a project by the French street theatre group, Royal de Luxe.

During rush hours they took an unprepared public (chance passers-by on the Leien /

Avenues) by surprise with singular installations in which cars and people play the lead role.

Salon Cinema took place on a square in the inner city. It was furnished with sofas,

armchairs and the like to resemble a gigantic living room. A programme of video films,

preceded by short experimental films, was shown on a large screen.

Applied Art

The driving force behind Fashion 93 was Linda Loppa, professor in the fashion department

of the Antwerp Academy of Fine Arts. In the last decade, this fashion department has

produced internationally-renowned designers.

The retrospective exhibition 30 Years of Academy, 1963-1993 showed photographs, designs

and drawings from each academic year during that thirty-year period. The exhibition of

Installations enabled visitors to share in the artistic process of fashion making.

Fashion Photography brought together work by six well-known Belgian fashion photographers.

Fashion 93 also comprised a special edition of the annual fashion show when students from

the academy show their designs to the public.

The second Applied Art project dealt with silver manufacture. The Arts and Crafts

Department of the V.I.Z.O. (the Flemish Institute for Small Businesses) initiated A Glittering Feast

project. A European competition was organised for the manufacture of new silverware. The organisers received 109 entries from every corner of Europe. An international jury selected work by thirty, mainly young artists.

The Multi-Faceted City

The some 150 projects included in the Peripheral Programme of ANTWERP 93 were non-

commercial, freely accessible, apolitical, high quality, artistically or culturally associated,

appealing to an international public and taking place in Antwerp. The chosen events were

certainly not small or second-rate: 150 Years of Zoo, Eurosail, the exhibitions organised by

the Diamond High Council and by the municipal museums, several foreign projects (EC

Japan Festival and Japan Week, Shanghai Week, Greece in ANTWERP 93).

Antwerp itself, its buildings, streets and squares, served as the stage on which the events

of ANTWERP 93 unfurled. That stage had undergone something of a transformation, the

city had spruced itself up for the festival. Many projects that had already been planned

were accelerated because of the cultural year. They gave the city a facelift for 1993, but

they also produced lasting results in terms of extending or improving the urban infrastructure and the urban image for the future.

A campaign for art: Communication

The efforts of ANTWERP 93’s press department resulted in wide media coverage: approx.

8.000 articles and reports in the national press, and approx. 13.000 articles and reports in

the foreign press. Moreover, just about all the communication methods were employed, in

so far as the budget allowed: brochures, leaflets, magazines, posters, radio and television

advertising, advertisements, mentions in the publications of third parties, stands at fairs,

flags, slide shows, etc.

In general ANTWERP 93’s communications succeeded in getting the message across to the

public.

The ARTwerpen logo reflected both the choice of art and the city of Antwerp. The

general campaign showed that ANTWERP 93 was looking to examine the place of the arts in

society. Questions were asked: ‘Can art savethe world?’, ‘What is beautiful, what is

ugly?’, and the like.

ANTWERP 93 had a strong presence in the cityscape with logo flags: festive, without being intrusive.

Conclusions?

ANTWERP 93 was a large and complex project. Anyone who cares to refer back to the

programme will see that it clearly reflects the policy plan in tangible form. The programme centred on art, stimulated the discussion about the place of art in society, showed a good deal of contemporary work by young artists and also gave many artists the opportunity to create new work. It showed Antwerp and Flanders to the world and brought the world to Antwerp. As a spin off from the Cultural Capital of Europe nomination,

Antwerp enjoyed considerable interest from tourists in 1993 and the event as a whole

clearly did much to enhance Antwerp’s image.

« Αμβέρσα 1993 Eric Antonis | Singling out the Book: Discourse and LIterature »