Mary Clow about the Mount Athos exhibition

Melina Mercouri died in 1994, but her final act is only this year being played out. With her famous persistence - and glorious laugh - she persuaded the EC to make Thessaloniki, the second city of Greece, "Cultural Capital of Europe l997".

The north-south divide operates as fiercely here as in Italy, though it is less well known. Athenians sniff at Thessaloniki (founded 315BC) as nouveau and corrupt. Thessalonicans retort that, as a major European commercial centre, they do not, like the south, pander to tourism for their olives and ouziki. Rebuilt since the terrible earthquake of 1978, their city bursts with pride. On summer nights, the streets of Ladidika - the old Jewish quarter, now the hub of bars and restaurants - swarm with well-dressed citizens out to enjoy themselves. But behind the area's picturesque old houses, the horror of the Nazi round-up of an ancient Sephardic community whose roots went back before the Apostle Paul still leaves a shadow.

Possibly, the central government's payments to prepare Thessaloniki to be Cultural Capital evaporated before essential work was carried out. Certainly, the mosaics are obscured by scaffolding, the oldest churches in Christendom are often closed, and many events were allegedly cancelled when the venues simply did not yet exist. But it cannot be denied that the notorious stench of the vast Gulf of Thermaikos has been cleaned up, so that even on a warm night, the seafront is strollable around the shining walls of the landmark White Tower.

To make the three-hour bus ride to Mt Athos from Thessaloniki is to time- travel back 10 centuries to one of the world's last undefiled theocracies, a source of mystery and myth, the Garden of the Virgin, the Holy Mountain: Athos. Keeping a discreet distance from the shore, a ferry chugs along the peninsula, which climaxes in Mt Athos itself, rising sharp-sided to 2,030 metres above the raging Aegean.

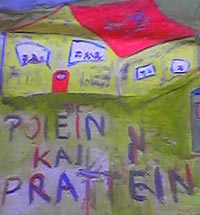

Once seen, the distinctive memory of the peak haunts the imagination, but no more intensely than the man-made phenomenon of the monasteries that perch tenuously on the clifftops and pinnacles of the Athos shore. Like fortified cities in a medieval painting, they are calculated to inspire awe and to proclaim impregnability. Sheer, windowless walls rear up into the sky to a safe level where spindly balconies jut out, clinging like bats. Crenellated fortifications overtop red-tiled roofs. Multi-storeys overlap each other, defying gravity or conventional engineering, like the Potola of Lhasa with rooftop palm trees. And everywhere there are churches upon churches, from minute chapels to vast basilica, crowned with an unending succession of Orthodox domes in red and white, emerald and turquoise. Twenty monasteries are still active, housing 1,500 monks, all dedicated to the Virgin, on a 50km promontory where nothing female may set foot, hoof, claw or paw. Hence an exhibition to bring the glories of Athos out into the light.

"Treasures of Mount Athos" is the crowning achievement of Thessaloniki's year as Cultural Capital. After years of discreet persuasion and tightrope- treading negotiation by the Ministry of Culture, the Holy Community has been induced to release thousands of its most exquisite possessions to be displayed for six months in the Museum of Byzantine Art, completed recently by the architect Kyriakos Krokos. With a delicacy suggesting a subtext of difficulties overcome, renowned Byzantianist Manolis Chatzidakis says: "The phenomenon has been kept for centuries essentially inaccessible to lay visitors from the outside world and totally inaccessible to half the population of the human race."

The very opening of the exhibition itself had, for an important international art event, unusual features. Dr Victoria Solomonides, the Greek cultural attache in London, chose her words carefully: "It was a mixture of religious festival and art exhibition - rather extraordinary - with droves of monks." It seems that, to avoid the indelicacy of literally rubbing elbows with "half the population of the human race", a dress code of long sleeves was imposed. And, for once, the female uniform of minimalist black and big jewels would describe most of the men.

As for the exhibits themselves, no hyperbole could exaggerate their splendour, but extracting them from Athos was "a Byzantine drama" says Panos Koulermos of the design team of four who finally had six weeks to mount the show and worked 16-hour days on shifts round the clock. Monks live in eternal time, not adapted to mounting international exhibitions; in places, tracks had to be cut to take the art out by four-wheel drive from the largely roadless peninsula.

The selection of items was a collaboration between the Greek Archaeological Service and the Holy Community who defined what they could lend. They are a powerful body, independent even of the government of Greece, so while many treasures were excluded as clearly too fragile to be moved, there is no question as to who made the final choice. Ironically, though, once the exhibition opened, rivalry grew between different monasteries vying to display their collections, and the exhausted designers had to find ways to cram these afterthoughts into showcases which, for security reasons, took an hour to unseal. Another unique problem was how to dissuade the visitors from kissing the exhibits, and tactfully constructed barriers were devised to limit the pious to crossing themselves without setting off the alarms.

Financing was shared between the EU and the Greek government. The most expensive item was insurance cover for priceless objects that had never before been valued, and this was borne by the government. No one can (or will) say if the monasteries themselves were financially rewarded for their co-operation, but it has been observed that one - whose library, claimed to rank third in the world, rested on open shelves - is now getting state-of-the-art facilities.

Whatever the tortuous difficulties overcome, the presentation of the exhibition is of the highest international museum standard, unfolding through six galleries the drama of Athos. Starting from the architecture of the monasteries with photographs and plans, the journey explores the ecological time-capsule of terrain virtually ungrazed and unfarmed for 1,000 years. Moving through evidence of the living conditions of the monks, with tools used for production and preparation of food and wine, it is impossible not to feel humbled by the battered bowls and platters mutely suggesting generations of use and poverty.

Then the splendour begins, and it is clear that the monasteries have been unstinting in the release of their most exquisite possessions. The categories range from sculpture, wood-carving, books and manuscripts, to wallpainting, embroidery, liturgical objects in gems and precious metals, and, finally, a millennium of icons. Included are many secular glories, particularly in the area of literature. Nearly all the ancient Greek classic writers are here, and the exceptionally rare De materia medica of Dioscurides, in manuscript from the 15th century, is considered the most precious volume on Mount Athos. Among printed books is a complete Homer of 1488, its pages as crisp as when they first left Florence. Most poignant of all is a Great Dictionary - one of the world's printing masterpieces - produced in Venice in l499 under the patronage of the Grand Duchess Anna Notara, who had escaped the Ottoman capture of Constantinople in which all her family perished. Among precious objects, there is the famous "Jasper" - once the wine cup of the 14th-century Despot of Mystra, believed to cure poisoning.

Seventy-three conservators are credited with cleaning and restoration, most of it done in situ within the territory of Mount Athos, where monks joined laymen in this delicate work. The Greek archaeological service maintains a permanent presence on the peninsula, continuously identifying, cataloguing and preserving in co-operation with the monasteries.

International scholars have, of course, been browsing in the monks' treasuries for centuries: unfortunately, some of the less scrupulous departed with keepsakes. Professor Grigoris Stathis of Athens University has spent 27 years cataloguing the unrivalled music collection. He refers grimly to "manuscripts which in some way or another have been smuggled out of Athos".

Another deeply felt reservation of Orthodoxy blocks entrance to scholars as much as to tourists. In the Eastern Church, the function of sacred art is far different from in the West. An icon is regarded as a window into another world. Emphatically never worshipped for itself, it is revered as the reflection of the religious subject it represents. Bishop Kallistos (Timothy Ware) of the Greek Orthodox Church in Britain neatly explains by quoting the 17th-century English poet, George Herbert:

"A man that looks on glasse,

On it may stay his eye;

Or if he pleaseth, through it passe,

And then the heav'n espie."

Above all, an icon is never a museum piece, and many Orthodox find it impious, even offensive, to present it in that context. For many years, this isolation contributed to a Western ignorance nurtured on the disdain towards Byzantium of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. As Gervase Mathew put it: "A travesty of art history fitted admirably with the travesty of cultural history to which Gibbon gave its English classic form."

It seems the dam has finally burst. In 1994, for the first time in 20 years, the British Museum mounted an exquisite show of Byzantine art and culture, entirely from British collections. This spring, New Yorkers queued to gasp at the Metropolitan Museum's "Glory of Byzantium" exhibition, an exploration of Byzantine culture ranging from Russia, Scandinavia, and Central Europe, through Greece to the Middle East and North Africa. There is more to come. The strength of international interest has taken the museum in Thessaloniki by surprise. With another two months to go, the excellent English-language catalogue (pounds 30, weighing 3 kilos) is sold out and reprinting fast.

The Greeks have historic memories that make the Irish look amnesiac. The atrocities of the Fourth Crusade (1204), which pillaged Athos, are rawly recalled, and our enthusiasm for their Byzantine culture has taken them by surprise. Yet as much as nature on the Holy Mount is a precious resource in our ravaged world, so are these freshly revealed treasures. One of the holiest icons of Athos, which is not in the exhibition, is the miraculous "Axion Esti" - named after a great acclamation from the dawn of Christianity which our Book of Common Prayer robustly translates as "It is meet and right!" Odysseus Elytis won the Nobel Prize in 1979, principally for his long poem with this title, in which he says:

"...Helen's neck like a long shoreline

The star-studded trees with their good graces

the musical notation of another cosmos

the ancient belief there exists forever

what is very close by and yet invisible..."

No longer

"Treasures of Mount Athos" is at the Museum of Byzantine Culture in Thessaloniki until 31 December. Enquiries: 0030 31 870 829/30/31

Source:

« The exhibition of the treasures of Mount Athos | Exhibition about poet Elytis »