Mitja Cander: The Reanimation of the Town

Maribor 2012http://www.maribor2012.info/en/index.php?ptype=3&ntype=1&id=104

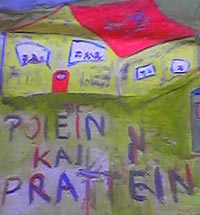

The European Capital of Culture can be just a title, a handy marketing and political move. The current crisis has done away with all arbitrariness; no one needs projects without substance anymore. The European Capital of Culture must truly come to life as a framework for the reanimation of the social environment. If we do not begin with the basic definitions, we will hardly be able to fit all the different viewpoints, proposals and projects into a thoroughly consistent and not only arbitrary framework. We must ask ourselves the seemingly naive question: what is actually at the core of the ECOC story? Let us leave aside for a moment all guidelines and documents – which are of course the fundamental normative and intellectual basis, yet their unbridled reproduction here would be pointless for the purposes of this paper – and ask ourselves about the three dimensions of the European Capital of Culture. ... Let us begin with the main determinant, culture. Our established perception of culture has two dimensions: officially it is recognised as a bulwark of national identity, which stems from a time when we, the Slovenians, did not have a country of our own and culture was recognised as a compensation for this shortcoming. As an undertone – and with its role in our nation’s defence diminishing – we perceive culture as decoration or, at best, as entertainment. The role of culture – especially in this time of crisis – must be re-established anew; we must redefine its social status. The general feeling of atomisation in a world, in which everything is totally connected with everything else, is a paradox of globalisation; and with its financial upheavals, this globalisation has now revealed its dark side also to the Western world. We too are constantly dividing ourselves: first it’s one and then some other occupational, social, generational and geographic group that gets blamed for all our hardships. Culture could be one of the few remaining frames of reference, one of the last places of meeting. This is due to the fact that culture, in its democratic foundation, holds the possibility for emancipation of different views and practices, or in other words: the cultural field is a potential intersection of identity circles. How often did we elaborate on creativity being a development paradigm, while we more or less openly doubted the sense of our own words, because our secret believe in economic growth, added value, and the like was too strong. But we did not believe enough in quality of life. Today, such a view seems much more realistic. The economy, which had before downright enchanted us, has lost its role as the only true and supposedly rational force, oriented towards constant development. Culture, in the broad sense of the word, can be a dynamic force, which opens up new spaces of coexistence through perpetual criticism and simultaneous creation. The ECOC must be an attempt to reconstitute society as a community. Therefore, for instance, the special emphasis on the inclusion of so-called vulnerable groups – from children and the elderly to handicapped persons and ethnic minorities – is not only a mere suggestion. The ECOC is an opportunity, a kind of creative laboratory, which is to show that culture actually can be a development potential of the future. This is not so much about figures and economic benefits – although they certainly are not negligible – as it is about the basic predisposition of culture to become a dynamic drive of the ever number social tissue. Not least this also represents a possible interpretation of the pure energy slogan. ... Too often do we take the European dimension for granted or use it as a rhetorical appendage. In these turbulent times, Europe is proving to be a very important vision of common existence. Fundamentally tied to it are the two other remaining determinants of the ECOC vision: culture and urbanity. The European vision aims at the coexistence of differences. This vision was exacted by a bloody experience of extermination and a more sophisticated experience of exclusion from the public space. Europe should facilitate the coexistence of generational, religious, ethnic, aesthetic and other differences; at the same time, it should be constantly embellished by the mind’s endeavour for the unknown, be it in the field of technology or in the arts. The European Capital of Culture must be able to encompass in its foundations this duality, plurality and ambition. When discussing the European dimension, we must consider both the involvement of European artists and experts in the programme as well as the potential participation of international audiences. As part of the European dimension we must also consider the different identity circles, which additionally define us and co-create the European context of Maribor and its partner towns; these include the Central European, Slavic, Alpine and Pannonian dimension. On a deeper level, we must consider the European dimension – plurality on the one hand and clear quality standards on the other – as a structural basis of the project. ... The third determinant of the ECOC, which we could also refer to as the vessel of the project’s realisation, is the town. In Europe, towns have a specific tradition, related to urban culture. We must ask ourselves: what is the story of Maribor – and of its partner towns – and what is its potential for the future? Maribor shares the fate of many post-industrial towns, which are painfully searching for a new identity. In a way, however, the fate of Maribor is rather specific: in this town, breaking with identity is a structural rule, dating back to the expulsion of the strong Jewish community at the end of the 15th century. More recent breaks are lucidly detected by Andrej Brvar in his work Mariborska knjiga (The Maribor Book). Crucial to Brvar’s analysis is the reference to Zorko Simčič’s reflection that Maribor is a town of undercut roots. Brvar dissects this reflection and finds that in the 20th century alone, Maribor broke thrice with its tradition – and these breaks were much more radical than they usually are – only to find itself in a kind of empty space and facing the question of how to continue. The first break happened after World War One, when the majority of the German population left Maribor, fundamentally changing the town’s national composition. The second break occurred during the German occupation in World War Two, which resulted in the collapse of the civic and unusually multinational town profile. And finally, the third break came with the end of Communism, when the town lost its proletarian or, as Brvar puts it, lumpenproletarian image. Brvar seeks the reasons for these unusually deep cuts in the special nature of the people of Styria and Maribor. He describes their character – and this is where the author seems especially inspired – as a hedonistic lethargy, that is, as a mixture between cheerfully giving in to the pleasures of the world and having a slightly dreamy absence and laxity. ... Considering the outlined predispositions, the mental framework of the ECOC in Maribor can be envisioned in the real world and in virtual space, as a kind of simultaneous opening of both. The town centre, symbolically emphasized by the medieval town wall, can be regarded as the heart of the ECOC. Not only are most of the institutions and the greater part of the necessary infrastructure located here, but the plan for the reurbanisation of European cities also envisions the revitalisation of historic city centres in general. A revitalisation process is successful when a city centre becomes not only a museum space but the focal point of creative energy and a place where people meet and grow together. In the case of Maribor, life is withdrawing from the town centre and moving to the shopping centres, which are as uniform as anywhere else in the world. The town centre must turn into a magnet. However, this cannot be achieved with investment interventions alone, although some are certainly necessary, as is the reorganisation of traffic. In 2012, culture must completely change the centre of town. Institutions and individuals have to be prompted to improve the existing cultural offer and prepare as many new and ambitious projects as possible. We must draw in exciting artists from Slovenia and from abroad, so that we can experience their viewpoints. The centre must burst into a quality social space. The events must fill not only the existing venues, but also new locations and the streets. We must weave an invisible net of performances and interventions, that indispensable shadow of utopia, which will raise awareness about past identities and show life the way. It is essential to achieve a high integration potential: we must bring together the performers involved, find points of contact between them and generally create a stimulating environment for such processes. Everything that takes place in the historic centre represents a basic layer; a thicket; an invisible, yet highly important net, which will cause artists and audiences, townspeople and visitors to become entangled in the ECOC. It is always an ungrateful task to talk in advance about the artistic surplus, which is always the crème on any ECOC cake. It is clear, though, that by increasing investments we can principally expect quality to increase as well. Whether we will indeed be witnessing a surplus, something which radically exceeds what already exists, we cannot tell for sure. First and foremost, we must establish a consistent story leading from the macro- to the microstructure and then leave it to art to discover and create all that is new. If the centre of town – as the heart of the ECOC in Maribor – will be torn between a kind of archaeology and dreams about the future, some venues and events outside of the old symbolic centre will be able to articulate a radical idea about the future. I am thinking especially about the devastated industrial, military, etc. buildings, which partially already have been – as in the case of the cultural centre Pekarna – and partially still could be filled with new contents for this occasion. In this context, the European Centre of Performing Arts, which is to be constructed in the Studenci district, presents an outstanding opportunity. With this building, Maribor would gain a contemporary multimedia centre, which could not only explore new approaches in the arts but would also develop into a point of observation of the old centre. As a result, the centre of town with all its inhabitants would ultimately turn into the main protagonist of the ECOC. Just across the new Centre of Performing Arts, on the other side of the Drava River, the new art gallery building – another important investment – is to be constructed. The planned new footbridge, which is to be located on the site of a former, long-gone medieval bridge, would symbolically connect two worlds: a world of fragile roots on the one hand and a world that ventures into the unknown on the other. Also connecting the two worlds would be a utopian idea, which Breton sums up in the verse: Not all of paradise is lost. We must expand the field of the utopian to the fringes of society, because that is where the culture of coexistence is primarily tested. It is the unrest of these fringes – which often manifests itself as helplessness, poverty, violence, hate or apathy, wrath, despair, (total) separation of individuals or social groups – that can become a source of new creation, a spring of social re-evaluation, a point of cooperation and a place of gathering. As a starting point, we will use the unexpressed, unarticulated or invisible realities of the fringes; and the shadows, which we will have to detect, name and recognise as the trapped and rejected potentials they really are, before carefully and subtly touching them, so that they can come to full life in their own way. Right there, where forgotten spaces and estranged individuals once used to idle away, something can instantaneously flare up and begin to sprout – something, which will turn from an abandoned and mocked district into a subjectivity of creation, meeting and re-evaluation of the ever changing conditions for freeing life. ... Apart from the real world, we must also not forget about the digital environment – on the contrary: it is crucial to realise that today the internet cannot be regarded merely as a means of promotion but as an independent, parallel story. This entire story will have to be managed, in accordance with the latest approaches, as a single programme entity. What will take place in reality will be in constant touch and exchange with the digital world, which will in turn take on an autonomous life of its own. The digital edition of Maribor 2012 will be based on different techniques of social media, which present an upgrade to traditional media in that they replace monologic communication with user interaction. Such techniques promote cooperation, interoperability, information sharing and community building. Users are no longer limited to being passive receivers but become an ever more active part of the project. The digital content of the Maribor 2012 project will be available for all major client platforms. Traditional computers are joined by new generations of increasingly efficient smartphones, while special attention must be devoted to the latest generations of tablet computers (for instance iPads) and e-book readers (Kindle, Nook, etc.). These devices will bring about a cultural revolution in the field of reading books, magazines and newspapers; at the same time they offer a new platform for digital artists. Instead of using the traditional keyboard and mouse, the latest devices rely on touchscreens, which enables them a wide range of new uses. Also new is the thin tablet format, which gives the new devices a completely different spatial effect when used in a certain environment, especially in comparison with traditional computers. ... I am convinced that Maribor can come to life on different levels, which all share the same story – the story of reconstructing a town through creativity. The described process of opening up the town – and all of Maribor’s partner towns – is a multilayered process of searching for but not also ultimately finding the answers to the dilemmas of the present. We must always ask ourselves what we want Maribor to be like in 2013, that is, a year after the ecstasy. This is that sustainable dimension which so many European documents talk about and which is not based only on infrastructural and economic benefits. There must be a leap forward in the quality of living in Maribor. The town must develop into a creative and socially sensible environment, open to individual initiatives and drawing people together; it must become a place of meeting and not of parting. This is a challenge for the town, the entire region and the whole of Slovenia; a challenge, which is not only a point of orientation but for the most part a realistically achievable project.

Submited: 8.11.2010

|

« Tomaz Pandur: the City of Future | Programme of Maribor 2012 »