Inofficial guide 2010 onwards

What follows are not official guidelines, but reflections of discussions which took place over time and which respond to what is claimed to be a successful implementation and yet thought to be a deviation from the original intention sought by Melina Mercouri and others at that time (1985):

- 2000 the nine ECoC cities with cafe 9 one of the most interesting connections between artists, new technologies and projects in the respective nine cities

- 2005 ECCM Symposium in Athens with a key theme being after the bombardment in London "street fear" but also how to create a network of networks with the concept of ECoC being adapted world wide

- 2006 Patras and the exhibition "20 years of history" curated by Spyros Mercouris and the online archive of heritageradio with its online publication: "Europe under construction"

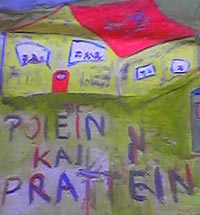

- 2007 when the ECCM Network and Poiein kai Prattein organized the ECCM Symposium 'Productivity of Culture' and the Kids' Guernica EXhibition in Athens 2007

- the creation of the informal network by Liverpool '08 and Ruhr 2010 under the premise we have nothing to learn from the older ECoC cities

- 2007 Sibiu and the coming into the scene the University Network of European Capitals of Culture

- 2010 what the Essen/Ruhr 2010, Pecs 2010 and Istanbul 2010 failed to undertake in order to substantiate the dialogue in Europe and the year of combatting poverty and social exclusion

- 2010 onwards reflections of the findings of the jury: evaluation and monitoring reports with doubts being raised with regards how San Sebastian and Wroclaw were selected for 2016

- 2011 the public consultation of the EU Commission for the years after 2019

- ongoing in search of validation of what can be claimed to be a succes with reports by Bob Palmer / Greg Richards / Diane Dodd the base line for studies about ECoC cities in need of due to the closure of the Documentation Centre in Athens (it existed only from 2007 until 2009), the way various ECoCs capitalized on their respective experiences e.g. Liverpool and Impact '08 by the Institute of Cultural Capital

Due to the tendency towards such evaluation and impact studies which use only measurable, quantifiable and hence commercializable measures, some other concepts need to be introduced if the negation of culture in the name of a culture which has to have value for the economy is to be halted and reversed. Some further considerations should be given to ideas and concepts still in need to be worked out but which indicate already something in need to be taken into consideration, if ECoCs are to claim really to have been successful during that one year. Alone the fact that investment in culture is a long term matter says already something about the need to adopt a long term strategy, something which has manifested itself in the new selection process to be used after 2019.

Working with change

Generally speaking, the model of success within the European Union has altered over time. Lille seems to indicate one leading model for the time being, as it underlines a combination of participation of people and incorporation of a larger area or territory than the city per say. The outcome thereof has been Lille 2030. Also significant after 2010, but already manifesting itself in 2007 onwards is the transition from the formal ECCM network to informal networks in which Lille playing besides Liverpool '08 and Ruhr 2020 playing a leading role on how terms are set, experiences passed on and support given due to links based on trust and friendship. That means in an overall sense the selection of future ECoCs is pre-determined very often by a collusion of interest in methodologies which have been proven to be capable of bringing about a successful year. Urban renewal is linked therefore to creative and cultural industries, participation to the digitial economy and intercultural dialogue to mobility of artists and artist in residence funding programmes.

ECoC cities as measure of time - since Athens 1985

Athens became the first city in 1985 to host such an institution. To capture the founding spirit, and the change it signifies, till then Europeans looked upon cities like Paris, London or Berlin as being the cultural capitals. The evolvement of the ECoC institution meant giving ever more small cities like Weimar 1999, Sibiu 2007 and as of late Leeuwarden 2018 a chance to put themselves on the European map. Naturally before that became a definite trend, the idea was to give Europe a cultural sense of unity rather than rely only on economic and political cohesion. Some of this change is noted by Matera in terms of cultural production being no longer linked solely to the big metropolis, since the modern communication age allows even cities till now on the periphery to enter the cultural production. It is a matter of dissemination. In the past the famous theatres and operas were restricted to the metropolis, and only slowly, as indicated by Saxony at the EU CIED conference in Leipzig 1999, when a law for the distribution of culture throughout the region was discussed.

By creating the institution of cultural capital designated on a rotational basis, but with changes in the selection process in store over the years since 1985, European Capitals of Culture have become within Europe a success story of its own kind. The fact that the project continues, and even has after 2000 at times two, if not in 2010 three cities holding the title at the same time, is significant enough. However, in addition, it furthers new types of cooperation while a growing tendency is to bring in as well cultural planning, cultural mapping and cultural policy as part of the long term development strategy of a city.

Alternative cultural orientations

Less noticed in the process is that these cities alter cultural orientations in Europe. They do so best when they succeed to linking the local level with the European level.

- a prime criterion put forth by the European Commission when selecting a city is 'citizens and the city' (applies to the selection process in place until 2019)

- the regional aspect as exemplified by Lille 2004, Essen / Ruhr 2010, and Marseilles Provence 2013 underlines a recognition that cities are becoming metropolis and that their hinterland is transformed into a broader context in order to satisfy the objective of cultural inclusion.

- cultural orientations need to be reflective of the changing European Agenda for Culture with the key terms being 'creativity' and 'innovation', although this does not suffice to explain the shift in priorities towards cultural and creative industries, in particular the film and media branches

- the dominance of the digital economy is not as of yet reflected in becoming more perceptive of media based arts (video installations), but this may be only due to the predominance of efforts to advance in the digitalisation of cultural heritage

- the links to education and social enterprises has also not been substantiated enough to ensure cross disciplinary forms of cooperation

- cultural identities articulated at European level is almost non existing while the national narratives continue to dominate; even Culture Action Europe fell into this trap when organizing its consensus around national representations and not representations of the arts per say and across the board i.e. national borders

The art of bringing people together

Already Athens 1985 brought artists and cultural actors not merely together in central places of Athens, but disseminated culture by including local theatres, small municipalities and yet to be discovered ‘hidden’ places e.g. a quarry converted into a theatre stage for Peter Stein’s ‘Orestie’.

Opening up to different dialogues

European culture is one of dialogue since Socrates. While the dialogue with reality presupposes involvement of the imagination so as not to be fixed to the mere 'given', poetry as logic of anticipation of the future has another role to what otherwise philosophy claims. It is an expression of trust in the senses and therefore in intuition as to what key words come up at any given time.

A practical example of engagement in dialogue: The three cities designated for 2010 as European Capitals of Culture (Essen / Ruhr in Germany, Pecs in Hungary and Istanbul in Turkey), were engaged as well in efforts to further cross-cultural dialogues or 'dialogues between cultures'.

The need to examine alterations to 'intercultural dialogue' since this concept subsumes to many other forms of dialogues so that it cannot do full justice to how cultures communicate with one another.

Cultural co-operation

The need for cultural co-operation between the respective two cities selected for each year is reflected as well in the cultural program they seek to implement during that decisive year.

Exchange of experiences

Also in the time before that, and during the years of preparation, during numerous conferences and meetings an exchange of experiences takes place. It could be called a kind of cross fertilization with the aim to foster mutual understanding but also uniqueness based on authentic cultural developments.

European Agenda of Culture (since Maastricht / Lisbon Treaty)

The term 'flourishing of culture' could be used to describe what is the aim of the European Union to foster this project.

Strategic dilemmas

- culture at local level i.e. cultural quarters and lively neighbourhoods

- culture at regional / European level

Both have to take into accont future tendencies since they will alter needs. For example, the philosophical idea of connecting people to the sea again in Denmark came from Oleg Koefoed who reflected upon the recent history since industrialisation and de-industrialisation. It poses a dilemma for future development plans e.g. should a port include both an industrial and tourist part, or be merely a tourist one.

- culture in international relations i.e. diplomatic efforts

Risks of civil society to be sidelined

Once powerful interests take over, and this is usually the case when 'inflationary spending' (Bob Palmer) impacts the organization, then civil society, and in particular cultural NGOs are left aside or else cooperation with mega NGOs sets in.

Gentrification instead of living cultural diversity

Once huge urban interventions take place, it means shanty towns disappear to make way for new urban development projects. To avoid gentrification a new key term makes its appearance, namely 'urban re-organisation'. This is not merely urban renewal brought upon by a European Capital of Culture as was the case in Glasgow 1990. Rather the disposition to a new type of governance using the cultural factor to alter conflictual zones between local indigeneous dispositions and a more pronounced inward investment policy to further a creative class in the sense of Richard Florida's thesis.

Type of culture being promoted

The usual dilemma is posed as if being between popular and elitist culture, when in fact cultural investments need to be made so that critical challenges to the way of doings things until now can be articulated. Quite a different case is when an open ended culture is being promoted by making precisely key investments with a long term effect. Here Bianchini makes the distinction between impact and alteration in the importance

Too many theoretical approaches reproduce political justifications for urban interventions by merging urban with cultural planning but which displaces in fact the artistic and cultural programme to be implemented. This reflects two things: a lot of money is involved when it comes to huge mega projects and the degree of urban interventions reflects inversely as well a growing superficiality / alientation to 'creativity / culture'. The outcome is what can be termed as 'official culture' with its own specific clients. It can take on as well distinct newly formed distinction by class in terms of preferred culture.

Cultural discrimination or the fate of the closed society

Once a highly speculative wave sweeps over a particular part of town or even the entire city, then it is no longer just in economic, but in cultural terms discriminatory. It pitches the indigeneous in a helpless way against these new forces of urban transformation. If it becomes an encroachment upon a certain way of life, those not willing to adapt shall end up at the fringe of society. Pockets of resistance may remain for a while and offer some authenticity but this only in relation to other areas of the city which have lost essentially in identity due to the neutral consumer culture. This has been the case of Marseille 2013. Instead of creating an inclusive culture discrimination between the rich and the poor has become even more pronounced than what existed before in that harbour city.

How to retain a distinctive cultural character - nature and aesthetics of resistance

Almost all remaining distinct areas have come under speculative onslaught e.g. Praga in Warszawa, Kreuzberg in Berlin or Kaszimircz in Krakow. It may even pit within these respective newly transformed urban pockets of resistance radical losers against radical gainers. The conflict unloads when locals attack a newly opened gallery or night club in an area known till then as being run down and often forgotten by the kind of urban development which had transformed cities in the twenties century.

Philosophical and Aesthetical principles behind a bid

A qualitative difference in a bid is made by having a concept which reflects certain philosophical and aesthetical principles. Thus European Capitals of Culture have become recently more focused e.g San Sebastian aims to use culture to overcome terrorism or Wroclaw adopted the philosophy of Adam Chmielewski to make the city become more attractive. But given the potential cultural conflicts as mentioned above, it requires a more realistic, equally further going philosophical reflections to ensure a sound cultural strategy. For how to engage those left out by the system? These are both the unemployed and the excluded minorities e.g. Roma. The concept behind the bid has to ensure that promotion of especially key cultural events does not neglect participation of the people. The aim should be to make possible experiences which allow a further going process as part of a promotion of ideas about place, its history and people in relation to Europe and the world. It goes without saying that this has to go hand in hand with dissimination of such knowledge which allows a deepening of the values of democracy while recognizing the need of criticism for audiences to sustain this process. as the air they need to breathe.

Conversion / Urban Transformation - continuity of identity and change

Essen / Ruhr 2010 is using culture to convert an entire former industrial region into a new cultural space. [1]

Such conversions imply urban transformations and therefore pose the critical question as to how a continuity of identity is maintained while all these changes are initiated and incurred.

Towards a synthesis of urban/ regional and cultural planning

Obviously cities need to engage themselves in a new modus of planning if culture is to play a crucial role in how a city develops and gives shape not only to its buildings but its various forms for future activities.[2]

See here the works especially by Lia Ghilardi, Franco Bianchini and others

Overcoming a cultural deficit

Obstacles to change can be linked to all kinds of cultural deficits: literacy, short horizon, resignation in the population, etc. to lack of funding and poor or no cultural infrastructure.

Unfortunately culture has been neglected since the beginning of the European Union. The situation has not become much better once culture was linked to the cultural and creative industries.

The entire economic side of the argument reinforcing that culture must have an economic value does not reflect sufficiently all the issues which are involved when it comes to allocate cultural resources. While the objective may be job creation, it is hard to prove at any time whether opening up and maintaining libraries has a real value in both the short and long term. Yet literacy does have an impact upon innovation.

In view of experiences made within the CIED project, any ECoC city should search for a balance between culture and economy best done by learning 'to use but not abuse culture'.

The European Union and cultural identity

Repeatedly Melina Mercouri is being quoted in her response when initiating the ECoC idea in 1983-85 to the fact that the European Union is much more an economic union than anything else. In addition to this, member states want to retain even today control over the cultural identity formation process. Equally citizens threatened by economic hardships express a fear to lose their cultural identities in an anonymous European super state. The selection process of future Cultural Capital Cities needs to take that into account. The wish to retain national cultures was one main reason for France and Holland to reject the EU Constitutional Treaty and why the follow-up, the Lisbon Treaty was rejected by Ireland in June 2008. The most obvious reason is the lack of citizen participation without which no European integration can take place.

Melina Mercouri intended to let people participate in Europe through culture but at the outset in 1985 not much thought was given to culture of any specific city; rather it was meant to show various European cultures or as it has become the case the culture of that specific city. It lacks the European dimension. As pointed out by Juergen Mittag (2008), it was most natural for the first selected cities to be already well known capitals e.g. Paris, Madrid, Berlin etc. [3]

The change in paradigm

All that changed when Glasgow became Capital of Culture. Glasgow used the designation to convert traditional places such as a church into a cultural centre and thereby brought back people into urban spaces long neglected by city sprawl. New was use of culture to inspire urban renewal. Bob Palmer succeeded with the support of the mayor to alter dispositions towards culture so that people could participate in creating themselves a meaningful life within the urban realm.

Every city defines its own success story

Every European Capital of Culture has its own success story but generally fails to sustain the process after the year has been completed. But by including smaller cities like Weimar, they could restore cultural heritage and pose anew the crucial question about the role of cities in shaping European culture? For instance, Weimar stepped out of the shadow of the East German past while it confronted the existence of concentration camps during National Socialism in direct contrast to Goethe and Schiller. Consequently Weimar brought with its motto ‘SALVE’ into public awareness not only the classical tradition, but Buchenwald existing at its very doorstep. Restoration of streets and buildings meant including cobble stones with names engraved of those who had died of AIDS. Of lasting importance is that Weimar banned all advertisement from the streets to leave truly visible the restored architecture. [4]

The European Caravan comes into town

When a city is Capital of Culture, then various European organisations, networks and institutions hold their meetings there. It brings Europe to that city and lets the visitors take note of the potentialities of that city for future events e.g. Sibiu 2007 in Rumania restored its historical buildings and churches, thereby putting itself on the map of future travellers.

In tune with poetry - only some cities

A novel, equally qualitative step was undertaken by Cork 2005: being small, it activated the local population to such great extent that since then the Irish Council for the Arts has taken note what cultural resources reside in that city. Cork organised cultural actions in all sorts of places, including hospitals and jails. For poetry and translation they developed a special system: foreign poets were translated by local residents who spoke that respective language and could act as mediator. It underlines one fact about culture: it is about compassion. For a particular poet to be translated there has to be a special love. It cannot be provided by superficial market orientated publishing houses. Rather it is about someone falling crazily in love with a poet in Rumania and doing everything to make that poet become known in the own language and cultural context. Such compassion and passion has to be nurtured and promoted very carefully. Without it cultural planning would be without substance.

Brussels together with eight others in 2000

When Brussels became with eight other cities European Cultural Capital City in 2000, the city was a typical example of fragmentation. While streets around Place Sablon exhibited high life, urban areas just around the corner were steeped in horrific poverty. Fragmentation was intensified by having 18 municipalities all with their own agenda and not really able to work together. Above all there is still today the tension between the Flemish and French speaking populations with their respective institutions more at odds with one another than trying to learn how to get along with the other side. Still another form of alienation leaves an imprint upon the city: the privileged Eurocrats compared to average Belgiums.

Most telling is the place where the European Parliament was built. Erected on grounds where a former intricate, indeed red light district existed, it is a story about eviction and destruction of local cultural fabrics. It has been captured by the photographer Marin Kasimir (1998). The story reminds very much of a similar fate of ‘Les Halles’ once Paris proceeded to expel the central market to the outskirts and thereby exported, as poet Baptiste Marray put it, life from the city. [5]

Now this area around European Parliament in Brussels is all hustle and bustle during working hours, but completely deserted at night. It exposes anyone walking there late at night all alone to all kinds of artificial existences. All that and more has to be kept in mind when Brussels became one of nine European Capitals of Culture in 2000.

Bob Palmer - legacy of Brussels 2000

Bob Palmer as artistic director of Brussels 2000 could apply the experiences he had made in Glasgow 1990. By then being a cultural capital had improved greatly since a huge budget was available to use art and cultural actions as a strategic way to go forward with urban renewal e.g. youth centres in abandoned areas. A great feat of Bob Palmer was to find a consensus between the two major linguistic and culturally distinct communities. They organised jointly actions. Above all Brussels united around a special parade which continues to date. The parade draws out the ridiculous parts in everyone and therefore makes daily life appear less weird.

Although Brussels 2000 was not capable of overcoming the huge gap between the Eurocrats and the local population, the city learned to see realistically its different functions and still provide room for discussions and participation. Based on ‘you never know for whom else such openings are good for’ Brussels came alive. People felt the city to be more of a challenge than a threat. Everyone felt life was coming back and with it some notion of security. Naturally that solved only temporarily the political, indeed linguistic and cultural dispute in Belgium but showed that French and Flemish actors can work together. [6]

Cafe 9

There was one special feat which European Capitals of Culture brought about in 2000: café 9. For two months all modern means of communication, video displays, voice conferencing etc. were used to bring the eight cities to talk about their various projects. In the end that amounted to 80 projects about e.g. ‘fear in the city’, ‘your favourite tramway route’ etc. When discussing the projects, people gathered in conference forums equipped with computers and video screens so that everyone could view the project’s visual and acoustic content while following the general discussion. One constraint was in place all the time: no one was to use the communication channels for personal messages. Café 9 demonstrated the possibility of cities to enter a horizontal discussion organized simultaneously across the board and therefore gave an idea how citizens could in future shape their respective urban agendas with prospect of creating together the European agenda.

The original concept of Istanbul 2010

Nuri M. Colakoglu, coordinator of Istanbul 2010 and therefore one of three European Capitals of Culture, explained at the ECCM Symposium “Productivity of Culture” that the city has adopted a philosophical approach by focusing on water, fire, earth and air to give shape to its cultural actions in 2010:

“The uniqueness of Istanbul 2010 is that it started out from creating a NGO and therefore represents a bottom-up process until the designation to be a European Capital of Culture besides Pecs, Hungary and Essen, Germany in 2010 was given.

To understand the various layers of history as evident in a city like Istanbul it should be reminded that there Hellenism, Byzantine, Ottoman and modern Turkey all of which have left their own unique imprint and which are still influencing how the city views itself in terms of history.

In terms of the complexities and problems to be faced in the present, the key question is how these problems can be overcome with the help of culture. Istanbul wants to set here an example. It can be done best by being a grass root, bottom up movement to allow for the participation of everyone.

Istanbul is a city of poetry and philosophy with many outstanding scholars and poets having created the basis for the approach adopted for 2010. In particular Aximander's definition of the four key elements, namely air, earth, water and fire shall be used to adopt the cultural program accordingly.

The Capital of Culture in Istanbul will not focus merely on the centre, but as well on the poor districts. Moreover it is the aim to involve the youth studying in 28 universities which exist in Istanbul. It gives an idea of the dimensions involved.” [7]

While it is very interesting to see how the concept for Istanbul evolved (bottom-up, NGO of Civil Society, aware of different layers of history defining the city while wishing to face the complexities and problems of the present, reaching out to the poorer districts), a real test of success shall be if the proposed thematic explorations will bring about cultural clarification of the real knowledge base needed by the city to be governed in the twenty-first century. By taking recourse to the ancient philosophical orientation of Aximander when referring to four elements, such a cultural strategy incurs already at the outset the well known risk of over simplification. Naturally for organisational reasons general themes can provide convenient ways to appeal to popular sentiment while giving space to specific events linked to themes of fire, air, water or earth. Much can be associated in accordance to them. Yet it is not clear if the themes shall be used as a constraint e.g. during the phase of the fire to deal only with fire, nor if the sophistication required for the cultural reflection of all four elements together can be brought about.

Cultural reflection is needed as basis for further understanding of life in the city. It has to be, however, differentiated enough. Here it can be doubted if these basic four elements will do. Since Aximander both society and science have moved on while languages in use no longer depart from such a basic philosophical premise. Or to put it in another way, an evaluative question can be what cultural experiences of these planned events around four elements shall enter during and thereafter daily life and alter the language of Istanbul? If after the year 2010 there emerges a new cultural structure for more sophisticated reflections, then it will be a success.

The test will be, however, if the year of being the European Capital of Culture will allow people of all walks of life in Istanbul come to terms with demands of life in the twenty-first century? If the outcome can be translated into new liveable forms, then something will have been gained. Otherwise the risk is to remember only at random what took place. There will not have been created a new knowledge base which can be used to integrate the diverse life elements prevailing in a city like Istanbul.

Reflections by Dragan Klaic about Istanbul

Seen from another perspective and assessed already as future European Capital of Europe Dragan Klaic, former President of EFAH wrote a report after he had visited Istanbul in 2005. There is much to be said for sticking to conventional wisdom when it comes to relating culture as does EU policy in general to cultural infrastructures, training and mobility and then to evaluate it in terms of public debate about culture:

“Inevitably, Istanbul’s becoming the Cultural Capital of Europe will depend on political influence, prominence and visibility, and yes, much energy will go into real estate deals and things that have nothing to do with culture but rather with the city’s infrastructure and logistics (as, for instance, a possible third bridge across the Bosporus). It is unrealistic to expect the Ministry of Culture and Tourism (that is its official name, and in this case indeed, nomen est omen!) will invest much in Istanbul’s cultural infrastructure. But efforts to secure Cultural Capital status might point out the drastic inadequacy of the cultural infrastructure sustained by the national government and – even more so – the cultural infrastructure supported by the City of Istanbul and its municipalities. It would reveal the dramatic absence of any cultural policy and stimulate the formation of broad coalitions to debate and articulate such a policy. There could be an orchestrated effort to balance investment in the tourist industry with investment in community arts and create an ambitious programme to develop public and private resources for contemporary creativity (which nowadays exist only as private largesse and not as a public responsibility). This could be an opportunity to remap Istanbul in terms of cultural infrastructure and ensure that its modest resources do not remain concentrated within the two square kilometres between Galata and Taksim or just a kilometre further north, while the Asian part and many areas on the European side lack any facilities. It could be a chance to upgrade professional arts education and integrate it better within the best of the existing universities. And the PR agency already contracted by the organising committee could perhaps begin by seeking to change attitudes in the popular media, which do not cover culture at all except as gossip or scandal.

Some of my interlocutors rejected any serious consideration of this idea as pure futility and an example of the touching naivety of an outsider who does not grasp how things work, how power is constructed and how public projects inevitably slide into private gain. Perhaps. But would those who adamantly reject any serious consideration of the Cultural Capital idea be willing to formulate their arguments against it and highlight what would be their own cultural development priorities instead? This would create at least some peg for public debate that is anyhow missing now.” [8]

Conclusion

There has to be added another point. If Istanbul is interested in carrying on the dialogue with other cities and serve as bridge for Turkey’s relation to Europe, and given its poetic-philosophical emphasis as outlined by Nuri Colakoglu, the city should try to include besides the four traditional elements as well discursive elements related to the dialectic of securalization. As the head scarf issue indicates in 2008, the Turkish society is undergoing a transformation in need of being explained and understood by European member states. The same goes for the many counterparts to Istanbul, namely other European cities. There has to be answered at the same time demands of how European Capitals of Culture can contribute to keeping the imagination alive in a world of not only consumption but also of moral rigidity. It ties in with what was just said above. A secular philosophy free from theology, as was the case in the Islamic world until the 9th century (and in sharp contrast to the mixture of theology and philosophy in Western Europe) entails quite a different cultural disposition than a religious force aspiring to determine the collective identity in quite another way. The question about Europe’s future may well be reflected upon in Istanbul come 2010. It is hoped that by being engaged in a dialogue with European cities, in particular the two other European Capitals of Culture, Pecs in Hungary and Essen / Ruhr in Germany while preparing for 2010, a common future in the making can be at least envisioned.

Hatto Fischer

(first drafted: 2010; updated 18.11.2014)

[1] See explanations by Bernd Fesel http://productivityofculture.org/symposium/a-z/bernd-fesel/#cv

[2] See official website of the EU: http://ec.europa.eu/culture/our-programmes-and-actions/doc413_en.htm

[3] Juergen Mittag (ed. (2008) Die Idee der Kulturhauptstadt Europas. Essen: Klartext

[4] This was something Antwerp neglected to do when cultural capital in 1993. The restored houses in the main streets were immediately hidden by advertisements which prevented the visitors from looking above ground level to see the upper parts of the buildings.

[5] For a very interesting photo documentation of this transformation of place see Marin Kasimir, (1998) “From Here to There”, Kunstverein Grafschaft Bentheim, Leuven: Exhibitions International.

[6] Text by Bob Palmer for the ECCM exhibition “Twenty years of History – a Journey through the world” with curator Spyros Mercouris for the ECCM Network in Patras 2006 from March 27th until May 17th 2006.

[7] Nuri M. Colakoglu, “Continuity of EU Cultural Policy: Istanbul – a European Cultural Capital already in dialogue”, http://productivityofculture.org/symposium/cultural-policy-2/

[8] Dragan Klaic (2005) “Istanbul’s Cultural Constellation and Its European Prospects”, A Report Commissionedby

« Program Cultural City by Jochen Gerz | Cultural Impact Assessment »