Croatian Candidate Cities for 2020

Dubrovnik, Osijek, Pula and Rijeka pass the ECoC 2020 pre-selection phase

June 1, 2015

The jury made up of independent experts has decided out of the nine Croatian cities that applied for the ECoC title, the four cities mentioned above made it into the short list. They have until Feb. 2016 to prepare further their candidacy for the European Capital of Culture for 2020. One strong recommendation has also been made by the jury, namely that for the second round cities are advised to hire European experts and not to try to go alone.

Bid - 2nd round

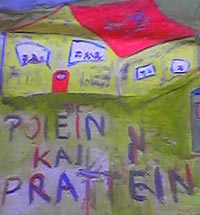

With a link between language and visual identity, the city Rijeka has put itself on the map. It was short liste. During the first round they prepared the bid all by themselves. As for the second round, they received the advise from the jury, that they should hire at least one European expert.

Consequently they hired Chris Torch who had been involved already in the successful bid by Matera 2019, and who has been active already in the city in 2004 and 2005 through European projects. Later on he was also invited by the University to lecture about cultural management.

Lately this over dependency upon the so-called European experts is being called into question. After all, these experts may ensure a language to which the European Commission can find easy access, and therefore feels better informed about the nature of the bid. It is, however, still another question if such a language can be relied upon as guaranteeing a substantial artistic and cultural contribution, and this with the full support by the local political forces, fore mostly the mayor included. The recent disaster in Matera with a newly elected mayor throwing literally out of the window the bid book which had been acclaimed by all, including the experts on the jury and who selected Marera to be ECoC for 2019, may serve here as an example.

The problem of an expertise driven language is that it merely promises on the surface to go conform with the six selection criteria and therefore with the idea the European Commission has developed over time as to which city should be the final choice in the final round. For sure, there have been surprises such as the selection of Leeuwarden over the other candidate cities in the case of Holland selecting a city for 2019.

Such a language may be suitable for monitoring and evaluation purposes. Yet how can this link between city, jury and European Commission ensure the promotion of substantial cultural content with strong signs of independence from the so called experts who have been shaping the EU agenda for culture too often completely independent from artists and citizens at local level?

The influence of someone like Bob Palmer cannot be underestimated. Moreover his presence alone guarantees a kind of attention by the press which others would not be able to muster. What this does in terms of contribution to the European dimension, no one is really sure. Still it is interesting to see a shift in focus when Bob Palmer refers to Leeuwarden of having won the bid due to no longer just striving towards participation of citizens but of engaging a special group, in this case farmers. Consequently engagement has become a leading term which will influence most likely the future selections of those candidate cities which fulfil best this criterion.

Indeed the negative side effects of this dependency upon European experts can be manifold. First of all, by not being locally rooted, they will hardly stay with the city to develop its cultural resources further even after the one special year of having been ECoC is over. Here Eric Antonis is an exception when he stayed on after having been the artistic director of Antwerp 1993 to the point that Bart Verschaffel would say whenever you talk with Eric, you feel like talking to the whole citiy. He made many more crucial decisions as Cultural Senator after 1993 and continued to invest in culture of Antwerp.

Secondly, the language they use is suited for EU policy making purposes but is hardly comprehendable for practical decision makers in the cultural fields e.g. museum director, gallery owner, theatre director. The EU speak is a coded language in itself, and as we can see in Greece, the models they advance are alien to what local populations feel to be their real needs in terms of cultural, economic, social and political development. The nuances in understanding this cultural complexity is not to be synthesized by such a terminology as 'smart city'. Yet the latter term has become a buzz word and guides not only decision making processes, but funding as well. Moreover it tends to convert the city to look very much the same as all others so that the one ECoC programme can hardly be distinguished from the other.

Further studies would be needed to reveal what consequences this compliance to the six selection criteria as interpreted by these experts has in the final end, but surely the lack of creativity is already an indication of falling victim to a kind of pattern which suits more the consumption of culture rather than shaping through culture the life in the city. If everything has to be novel and innovative, then there is the famous sentence by Adorno who stated once the new seeks only the new, then it is surely forced to flee back into old structures once it has failed to realize itself as the new.

Something similar happens when cities do not learn from previously made efforts but consider themselves to be so advanced or so rich in themselves that they do not need to enter an extensive learning process in order to understand what responsible role it is to be a European Capital of Culture.

Needless to say, the fact that there are two and now in the new selection process three cities per year which carry the title, the uniqueness is diminished and much of the same is in store. The pressure of compliance is simply too great while other forces exert tremendous pressures in only a certain direction which goes hand in hand with the over commercialization of culture. Here the EU Commission had posed in the past something much more progressive. At the beginning of the ERDF Article 10 Programme, it was demanded that projects should examine whether cities could learn to avoid over commercialization since this would lead otherwise to a destruction of identities, while at the same time the EU Commission was nevertheless interested at that time (1997-99) whether or not culture could be used to create new jobs? The latter prompted the Irish poet Brendan Kennelly to say the objective of all cities should be to learn to use but not abuse culture.

HF 6.10.2015

« Ireland 2020 | Rijeka 2020 »